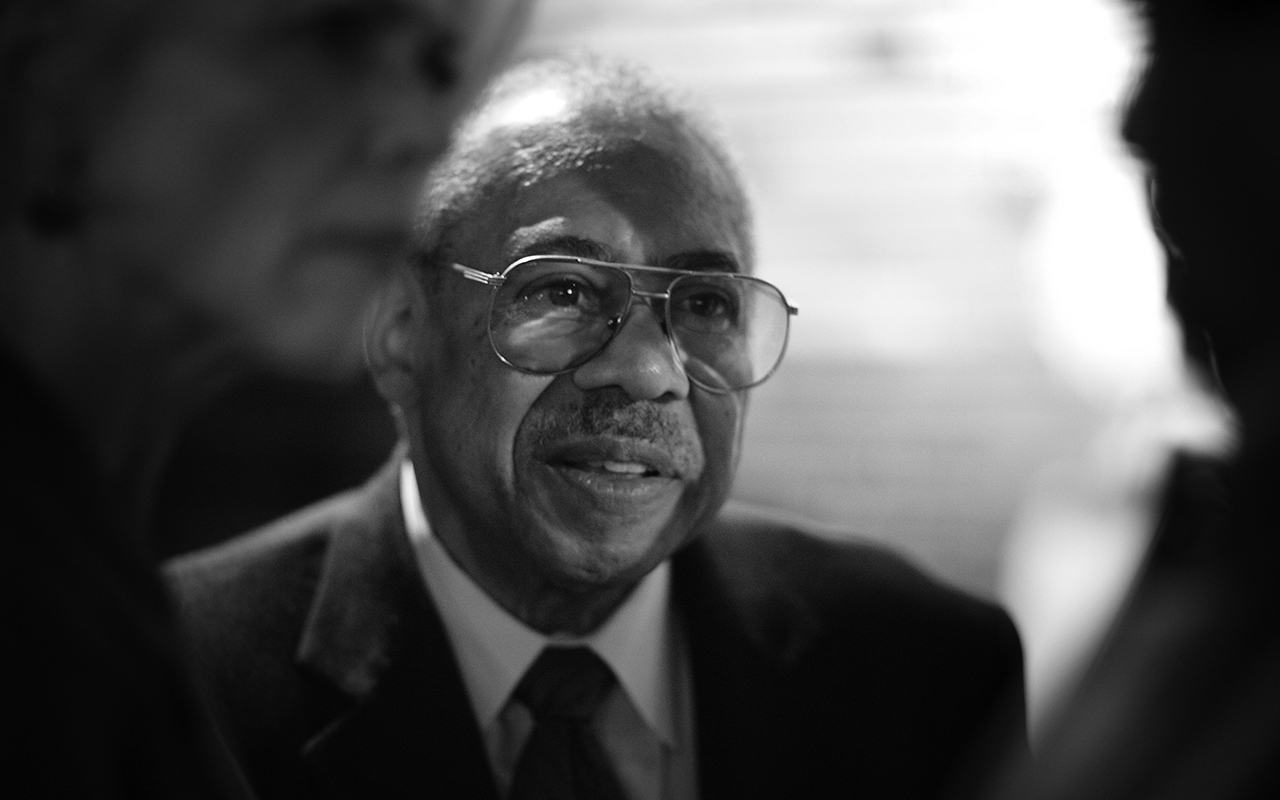

Buddy Catlett photo by Daniel Sheehan

If great musicians jam in the hereafter, the band just got more celestial. Its bass department has taken on one of the best, Buddy Catlett.

After some years of heart and other ailments, Buddy, an enormous figure in Seattle jazz history, died on November 12, 2014, aged 81.

Catlett had, through the first half of his career, an astonishing reach into jazz history as it unfolded, and then bore his experiences ahead into decades of performance and bandmateship in Seattle. He spanned eras and styles of jazz. Praise for him, as a musician and a person, has come from afar. Quincy Jones, Buddy’s childhood and lifelong friend, called him “one of the greatest bass players to ever take the stage.”

While Buddy Catlett was born George James Catlett in Long Beach, Cal., he came with his family to Seattle as a child. While at Garfield High School in the late 1940s, he played saxophone with Quincy Jones in Charlie Taylor’s band and the Bumps Blackwell Junior Band. In 1950, pleurisy sidelined him for two years and led to his taking up bass, although he maintained his horn chops throughout his life. Ronnie Pierce, himself an acclaimed Puget Sound saxophonist, flutist, and clarinetist, recalls that after Buddy took lessons from him at age 11, “we progressed through a lifetime of friendship.” He says “Tiny” Martin “was a master and taught Buddy how to get the tone out of the bass.” When he and Catlett joined the Bumps Blackwell Band, “We backed up Billie Holiday at the Metropolitan Theater, which was part of the Olympic Hotel. Then, a year later, the band with Buddy and me backed Billie Holiday again at the Eagles Auditorium on 7th Avenue.”

Catlett went on the road in 1956 with bandleader Horace Henderson, the younger brother of Fletcher Henderson, and then with guitarist Jimmy Smith and Latin jazz vibraphonist Cal Tjader. But Seattle reached out for one of its own. Quincy Jones asked Catlett to join him on what Paul de Barros called, in an obituary in the Seattle Times, his “short-lived but now-legendary big band” as it toured Europe with Jones’s Free and Easy Revue starring Sammy Davis Jr. Also on board were future Seattle stars, trumpeter Floyd Standifer and pianist Patti Bown.

After the show ended, the band remained in Europe for eight months, cementing reputations. In 1961, Catlett got a call from Count Basie, and joined his Orchestra. Buddy recorded numerous albums with the leader, including Li’l Ol’ Groovemaker and Ella and Basie, as well as Sinatra–Basie: An Historic Musical First in 1962.

In 1965 Louis Armstrong hired Catlett who played, recorded, and toured in that vaunted company until 1969. AllMusic draws particular attention to Catlett’s contribution to “Cocktails for Two,” “in which most of the theme is sipped as a bass solo.” (It’s on YouTube.) Thanks to his membership in Armstrong’s band, Buddy appeared in three films, including When the Boys Meet the Girls, of 1965.

He went on to work with a host of big-name leaders, including pianists Red Garland and Junior Mance, drummer Chico Hamilton, saxophonists Coleman Hawkins, Johnny Griffin, and Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis… There were many more: Booker Ervin, Mongo Santamaria, Phil Woods, Frank Foster… He appeared on more than 100 albums, backing the greats. Ben Webster, Anita O’Day, Sonny Stitt, Ella Fitzgerald…

Throughout his touring career, Buddy struggled with alcohol and returned to Seattle in the 1970s to recover. He began playing in a variety of settings, including with drummer Clarence Acox in the Roadside Attraction Big Band. Others collaborators included vocalist Edmonia Jarrett, reeds man Ham Carson, and Bill Sheehan’s fine Tuxedo Junction big band.

In his Seattle Times obituary, Paul de Barros records that during those years “wherever he played, national touring artists would come to listen.” Marc Seales told de Barros: “One night I was playing with Buddy at Tula’s. Wynton Marsalis came in and said, ‘I came down to play with Buddy.’”

For a 1998 article in Earshot Jazz, Catlett told de Barros: “A lot of my time feeling is from the Ray Brown tradition of being right on top of the beat. When you play like that, you have a tendency to run away with the time. But what you learn is that it’s the whole beat, including the decay, that you have to play.”

The affection that Buddy Catlett attracted from Seattle jazz musicians was legion. After all, he had schooled or inspired many. Drummer Greg Williamson, who with multi-horn man Jay Thomas recorded Catlett’s only album as a leader, Here Comes Buddy Catlett, in 2004 on Williamson’s Pony Boy Records, recalls first hearing Catlett who was playing with Floyd Standifer at the old New Orleans Restaurant site in Pioneer Square: “I convinced my mom to take this junior-high-school kid to the big city to hear the band. On hearing I was a drummer, Buddy asked me to sit in. After the tune he said to my mom ‘The kid plays good.’ I think my path was cleared with that one encouraging note.”

Horn player Jay Thomas recalls: “For as long as I can remember I heard about Buddy from Rollo Strand and George Segal and my father Marvin and many older musicians. I heard stories and tales repeatedly about Buddy Catlett. Buddy was always Seattle’s pride and joy.” As friends, “Buddy was always so supportive and encouraging,” Thomas says. “Buddy was like an older brother.”

Another frequent bandmate of Buddy’s, Brian Nova, recalls his bandstand shorthands, particularly “Well OK den” which, Nova says, “could be used when someone messed up a solo, or if someone really blew us away playing, or if someone pissed us off…” Eventually Nova asked where Buddy got the phrase, and learned it came from Catlett’s childhood neighborhood. An elderly neighbor would slowly drive his big-ol’ Buick to kids’ merciless teasing until one day some youths “were chillin’ around the old man’s car, so he goes outside and tells them ‘Get away from my car, you little rats!’ and one of the teenagers pulls his coat back to reveal a piece he has tucked in his pants, and the old man looks at the gun, then at the kid and says ‘Well OK den,’ turns around, and walks back into the house.”

Among the qualities Catlett often displayed was a wide-open mind for jazz styles. He told Paul de Barros in 1998 about living in New York in 1959 at Booker Ervin’s house and going repeatedly to the Five Spot to hear Ornette Coleman: “Every night, Monk and Trane would be sitting in the middle of the room, and they’d stay there all night. Ornette definitely had something going. People want to find out who you are, you know, so Ornette asked me to play. It wasn’t all that different, but the bar lines were! It was like thirteen-and-three-quarter-bar tunes!

“There’s a lot of things you can do, though, if you listen.”

Michael Bisio, who spent many years in Seattle as an avant-garde bassist, recalls that one day Buddy arrived at his house and began flinging packets of bass strings through the window. “He knew I was exclusively using guts at that time and brought them over as a gift,” Bisio says. “There were probably four complete sets of new old stock LaBellas from the 1960s, a slightly used set of Golden Spirals, a single new old stock G string Red o Ray… It was a lovely and generous gift, on par with Buddy’s everyday spirit and vibe. A man beyond beyond.” That he was open to any music that was good was evident when he joined Bisio in performing two-bass gigs together in Seattle, with our without other players.

As Bisio and many others can relate, Buddy Catlett’s humility was as memorable as his generosity. Catlett’s late-life companion Jessica Davis, who recorded interviews with Buddy for Black History Month and other historical purposes, says it was only after seeing reactions to him at jazz events, even from national stars, that she realized just how highly regarded he was: On one occasion, coming away from Jazz Alley, “I told Buddy, ‘You were quite a hit tonight.’ And, he responded, ‘Yeah. What do you know? Who would have thought?’”

Davis sums up the Buddy Catlett she knew through reference to a comment he made in an interview “that really resonated with me, about how he went to see Count Basie at the Civic Auditorium, and he was so mesmerized by the band’s performance that he almost fell out of the balcony. He followed that by saying, little did he know that he would some day play with the Count Basie Orchestra. That really stuck with me – he followed his dreams, and it wasn’t easy, but he was strong.”

Quincy Jones said in his “RIP to my brother and bandmate Buddy Catlett”: “We traveled the world playing the music we love. A lot of notes, a lot of laughs, a lot of great memories. We will all miss you Buddy, but you will live on in our hearts.”

“Buddy Catlett: Celebration of Life,” a musical tribute and jazz jam coordinated by Clarence Acox, will take place at Jazz Alley on Monday, December 1, 7-10pm.