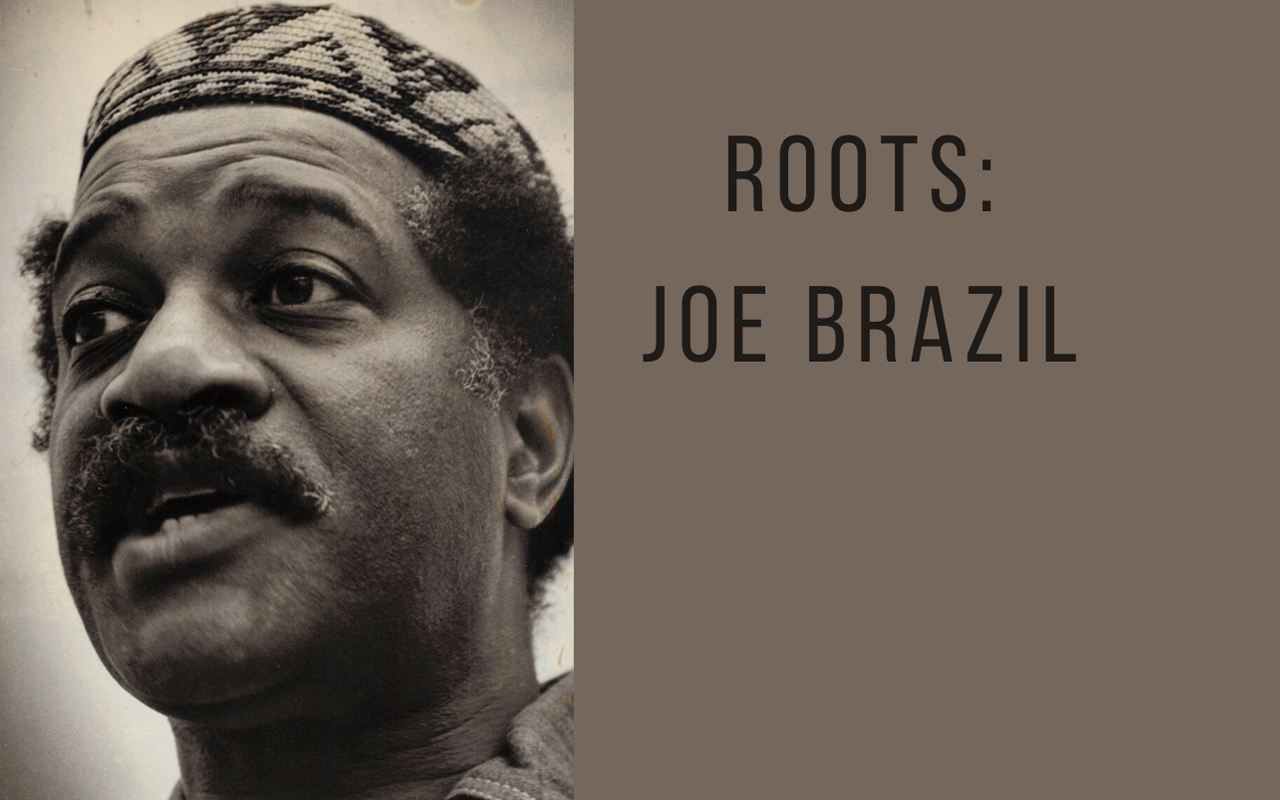

Joe Brazil photo courtesy of Paul de Barros.

Earshot Jazz is proud to share brief excerpts from the forthcoming book, After Jackson Street: Seattle Jazz in the Modern Era (History Press of Charleston, S.C.), by Seattle’s preeminent jazz writer, Paul de Barros. Picking up where Jackson Street After Hours (Sasquatch Books, 1993) left off, the new book will feature fascinating interviews with the familiar artists and under-sung heroes who shape this vibrant jazz scene.

BY PAUL DE BARROS

A few weeks ago while revisiting the interview I did in 1989 with saxophonist, band leader, and educator Joe Brazil for Jackson Street After Hours, I emailed former Garfield band director Clarence Acox for a clarification. Acox responded, “I’m glad someone is writing about Joe. His workshop preceded all the other jazz workshops in the area. He was a true visionary.”

Indeed. Long before JazzEd and the widespread fame of Seattle’s high school jazz programs, Joe Brazil confronted the racial and economic disparity in jazz education by establishing an accessible school where kids could learn to play jazz. Originally called the Black Academy of Music (later changed to the Brazil Academy of Music), the school had its heyday in the ‘70s when it offered a rehearsal band, music lessons, and workshops. The workshops were with the legendary likes of McCoy Tyner, Archie Shepp, Cannonball Adderley, Dizzy Gillespie, and a local faculty that included trumpeter Floyd Standifer, saxophonist Jabo Ward, bassist Milt Garred, guitarist George Hurst, and Brazil himself. Some of the students who passed through the Academy included the late trumpeter Ed Lee, tenor saxophonist Omar Brown, brass player Sam Chambliss, and bassist Doug Barnett Jr.

Originally from Detroit, Brazil came to Seattle in 1961. In 1965, he played with John Coltrane at the Penthouse, recording with him on the album Om (a reissue of the album is reportedly in the works). Brazil also taught at Garfield High School and the University of Washington, where his denial for tenure despite the enormous popularity of his jazz history class caused a campus uproar. Brazil passed away in 2008. For the most comprehensive information about his life and work, visit joebrazilproject.blogspot.com, maintained by Seattle saxophonist Steve Griggs. In the meantime, here are a couple passages from his Jackson Street After Hours interview:

“So many people would come to you and say, ‘Well, if I could just have had money to buy an instrument’ or ‘If I could just have had a teacher’ or have this, that or the other, ‘then I would have studied music’…So, the idea was to have an organization that had instruments, had a building, had teachers, and had equipment so that anyone that wanted to study music could never say, ‘I didn’t have the opportunity to study.’…It was called the Black Academy of Music. I think I was looking at something like either Batman or Superman, all them BAM!, BOOM!, WAM!’s, you know? And, somehow BAM stuck out. I got the acronym before I put the name down.”

“[Regarding the intensity of the music with Coltrane at the Penthouse]: When you’re really involved in the music, you’re not aware of the audience or self or whatever, because everything is clicking as a harmonious group. Now, mostly in the commercial scene, you’re trying to see who’s laughing, who’s buying beer, you know? You’re trying to make sure everybody’s happy and all that kind of thing. But when you’re really creating on a higher level like that sometimes—and I guess ‘Trane had done it many times, and I’ve had the good fortune, a few times, you know, of reaching that state—so you don’t really recall it totally. At least I don’t. And, McCoy said he didn’t. ‘Trane didn’t want to hear it back mainly because, he says, ‘Well, I just don’t want to be influenced by those kinds of things.’ But one time he says, ‘I’ve often wondered what my music would sound like if I heard it the first time.’”