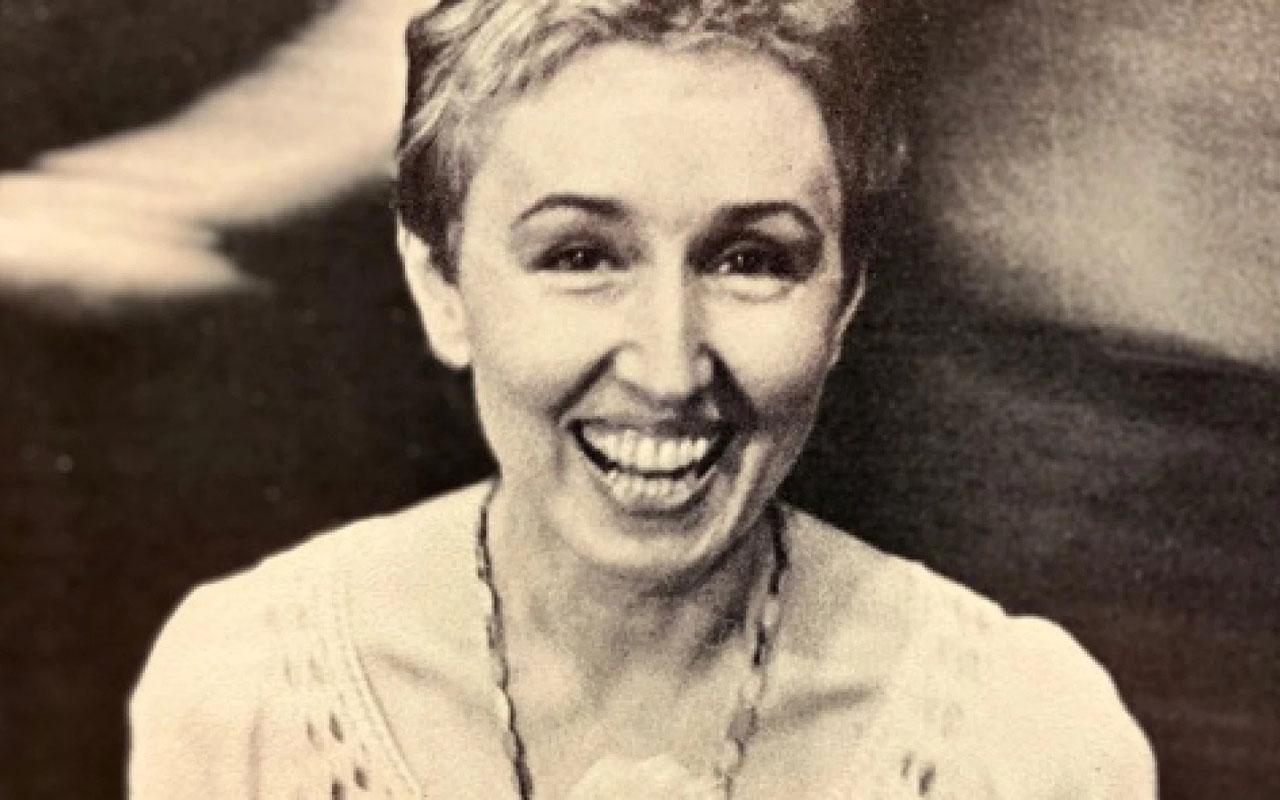

Joni Metcalf photo by Bob Peterson

Earshot Jazz is proud to share brief excerpts from the forthcoming book, After Jackson Street: Seattle Jazz in the Modern Era (History Press of Charleston, S.C.), by Seattle’s preeminent jazz writer, Paul de Barros. Picking up where Jackson Street After Hours (Sasquatch Books, 1993) left off, the new book will feature fascinating interviews with the familiar artists and under-sung heroes who shape this vibrant jazz scene.

The first person I called when I was asked for a follow-up to Jackson Street After Hours was the great singer, pianist, and Cornish teacher Joni Metcalf. Though Jackson Street had included Joni’s poetic liner note from her 1969 solo album, Joni, we had never sat down for a full-fledged oral history interview. To my delight, our talks inspired her to write a memoir. By way of commemorating Joni’s rich life in Seattle jazz, which ended November 15, what follows are (lightly edited) excerpts from that unpublished work.

1946. Music was coming from somewhere out on the street. I opened the front door and saw a neighbor washing her car, a red Ford convertible. She had a record player nearby and the music sounded like jazz, but not the swing band type I was used to hearing. Being an inquisitive 15-year-old, I crossed over and asked her what she was listening to. “That’s bebop.” She mentioned Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, new names to me at the time, but names that I have followed all my life since. The giants. A few years later, at the Seattle Civic Auditorium, Charlie Parker appeared with Jazz at the Philharmonic’s touring show. I went backstage at intermission and saw him asleep in a chair.

1952. I met my future husband Chuck Metcalf, an architecture student at UW, by hiring him as a bass player. Chuck was living in a weathered storefront in the University District at 3809 Brooklyn Ave NE. The store was a hangout for both musicians and architecture students. Paul Neves, pianist, lived across the street. The outside looked like it was abandoned, but the inside was decorated so artistically it could have appeared in Sunset Magazine. On a student budget, he had papered the walls with free foreign newspapers from the International District. Straw mats covered the floor. A large mattress with a colorful spread was in the corner. Bamboo shades and gauzy curtains covered the two large display windows, one on either side of the front door. Hanging light fixtures had white, rice paper shades. The front room was divided in half by a wall of stacked orange crates. The open side of the crates, facing the back, serve as both a bookcase and headboard for the other mattress with a colorful spread, his bed. On the north wall hung a 6×3 ft. oil painting. It looked much like the Milky Way, but of many colors. He had painted it in his early college days. 1981. One of my band members told me the guys in the band wanted more direction from me. On Monday, I was heading to Port Townsend to teach four days of classes as part of the Centrum Festival. On Saturday evening, we would be opening for Johnny Griffin, the headliner. We’d be playing what turned out to be the best concert of my career. That week, between classes, I planned for Saturday night, creating and timing the set list, deciding how long each solo would be and by whom. When the guys arrived, I explained exactly how it would be going down. They listened carefully. The concert was in a huge tent which held a far larger audience than any I’d ever played for. My synthesizer and a grand piano were on the stage. We set up and then the lights began to dim. The guys looked at me and I counted off the tempo. Everything went as planned. I had no nerves. All five of us played well. At the end of our last piece, the huge crowd erupted with applause, stood up and wouldn’t stop until we played an encore. I saw Johnny Griffin looking at his watch. We played another composition of mine and this time, with more loud applause, we left the stage. A crowd gathered around us while Griffin’s band was setting up. One person pushed forward – Jim Knapp, my boss at Cornish, a man of few words. He looked me in the eyes and said, “Nice set!” I can still hear those words. “Nice set!”