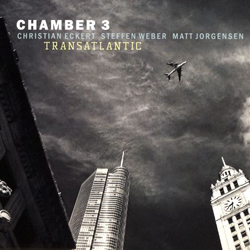

Chamber 3

Transatlantic

OA2 Records

Like a longstanding relationship between good friends, Transatlantic impresses with its ease, candor, and respect that each distinct player shares for one other. As the title suggests, it’s an album merging cross-global talents. The Chamber 3 collective consists of German players Christian Eckert on guitar and Steffen Weber on tenor saxophone, along with Seattle artists Matt Jorgensen on the drums and Phil Sparks on bass. This is the foursome’s second offering following the 2014 album Grassroots.

Transatlantic is sharp, thoughtful, and vivifying with a modern edge. The project naturally lends itself to a democratic sound, as three of the musicians are composers, while all four players’ music resonates equally. The opener, “The Sparks” by Jorgensen, is a lively mid-tempo piece that juxtaposes jaunty bass, guitar, and drum instrumentals with a saxophone that pleasantly mingles the plaintive with joyfulness.

“Chillaxed,” a piece by Eckert, lives up to its name with a slow-paced style. It slinks by with a gentle, but thoroughly satisfying, walk-in-the- park-sort-of-sound, with attractive sonic interludes offered by each artist. “Hesitant Spring,” also by Eckert, is one of the most beautiful pieces with its memorable melody; tender and wistful with an elegantly paired soulful, slow bass and guitar that lay the groundwork for the exquisite drawn-out saxophone. The persistent yet reverent drumming keeps things balanced all the while. Weber’s arrangement of the classic, “When You Wish Upon a Star,” is like the lucky hidden charm in a cake. It surprises with a recording of urban traffic sounds to open and then is fleshed out by the confident and contemporary playing by each musician. This piece could end up as part of a film track contrasting Pinocchio’s hopeful sentiments with realism. Transatlantic is thoroughly engaging and full of nuggets of creativity that only get better with each subsequent listening.

–Lucienne Aggarwal