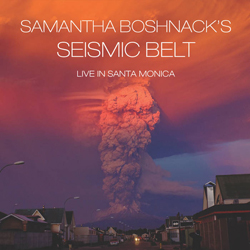

Samantha Boshnack

Seismic Belt: Live in Santa Monica

Orenda

Trumpeter and composer Samantha Boshnack takes the subject of volcanology—the study of volcanoes—and addresses the unpredictable, yet law-driven nature of the earth’s surface through her septet’s fluid improvisations on her latest release, Seismic Belt: Live in Santa Monica.

Written with the help of the 18th Street Art Center’s Make Jazz Fellowship Commission, Boshnack’s loose suite represents a huge leap forward in her ensemble writing, judiciously utilizing the environment as a source of inspiration, letting the ingenuity of her band of LA regulars draw both fear and humor from the shifting ground of her material.

Boshnack balances her brass with reedman Ryan Parrish on tenor and baritone saxophone. Parrish’s laidback sound on baritone compares well with Boshnack’s wry, concentrated tone on the multipart “Summer That Never Came,” a third-stream threnody written after a volcanic eruption in Iceland in 1783.

Boshnack’s habit of grouping instruments of parallel or disparate timbral quality extends with the addition of two string players: Paris Hurley, classically trained violinist and touring member of the punk band Kultur Shock, and violin/viola player Lauren Baba, award-winning composer and leader of her own big band, theBABAorchestra. On the Latin-inspired “Choro,” Baba gives an exceptional solo, filled with brief harmonics, double stops, and slight melodic twinges, ending in a final gesture like a silhouette slipping into darkness.

Up-and-coming pianist Paul Cornish, along with LA session drummer Dan Schnelle, form the true “rhythm” section in the midst of Boshnack’s shifting harmonic strata. Schnelle proves covertly funky throughout, pulling off snare hits and double time triplets for a kind of re-wind effect on the jump chorus for the opener “Subduction Zone.” Cornish gets his grip on the piano tradition from Oscar Peterson to Cecil Taylor with his sprawling, comprehensive solos. On the highly composed “Tectonic Plates” he varies a theme with contrapuntal lines, which break up in manic clusters and crossing harmonies to match the tune’s stunning final mash of melodies.

Boshnack draws out remarkable performances through her compositions, as on the standout track “Fuji.” The use of traditional material harkens back to Thelonious Monk’s “Japanese Folk Song” and its volatile rhythms inspire standout performances. Far from novelty, it’s folkish call and response sustains a large jazz ensemble at its best: erupting in the convergence or divergence of composition and improvisation.

–Ian Gwin