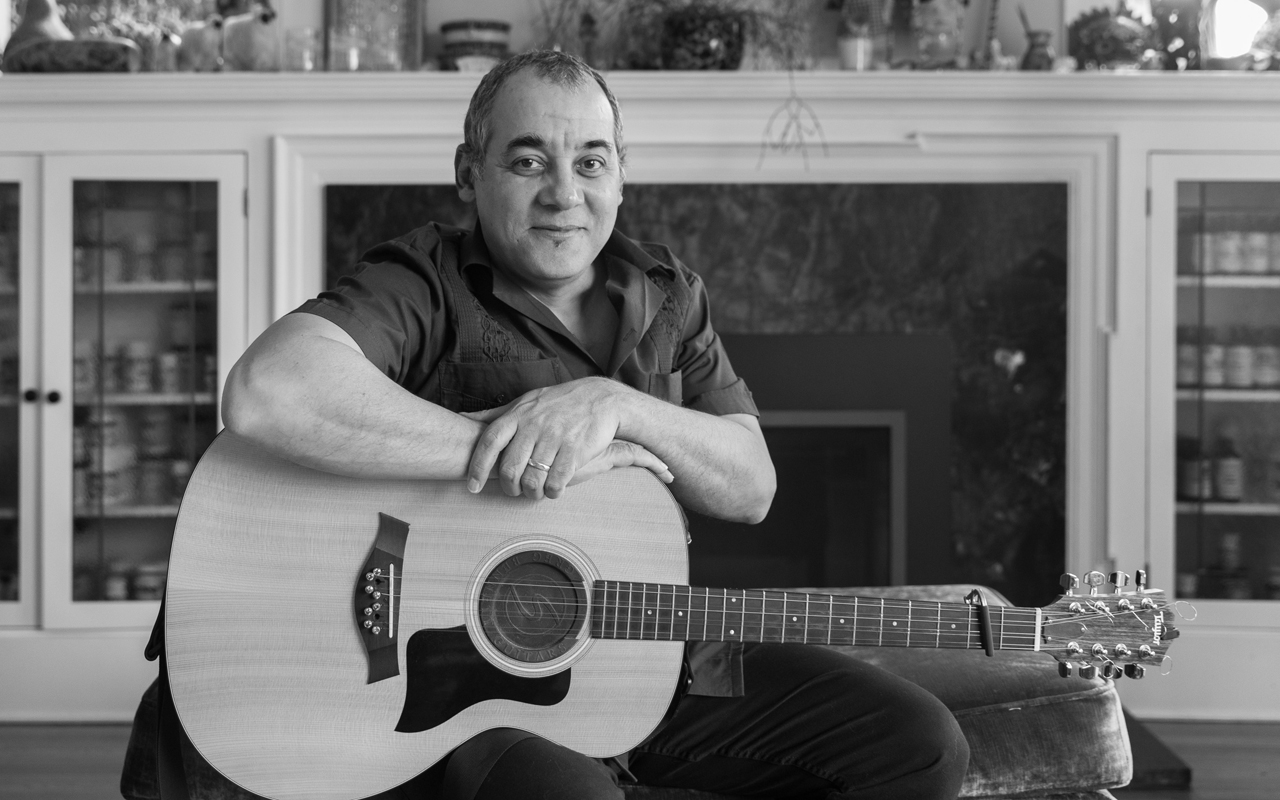

Kiki Valera photo by Daniel Sheehan.

By Paul Rauch

Son Cubano, the traditional music and dance from the hill country of eastern Cuba may well be but a distant tributary to the jazz tradition that came to life in New Orleans. Yet the unmistakable Son clave rhythm that accompanied Afro-Cuban sounds to arrive through that delta port is a significant ingredient in the diverse gumbo of influences that convened to create the blues and jazz tradition.

The ethnomusicological pathway that feeds this contribution requires some in-depth recognition. In Seattle, we are very fortunate to have a direct taproot into that tradition, in a musician that performs well within the Son tradition, while at the same time, expressing it in modern terms.

Kiki Valera is a master of the Cuban cuatro, an eight-string instrument with four courses of double strings. He is the eldest son of the cross generational septet, La Familia Valera Miranda, whose history dates back to the 19th century. The story of how he gained acquaintance with jazz music, and came to be a resident of Seattle is quite remarkable. Known as one of the true masters of the Cuban cuatro, his sound has been echoing through venues in the city for nearly seven years now, and has manifested itself in a brilliant new album, Vivencias en Clave Cubana (Origin, 2019).

Seattle would seem an odd landing place—a remote outpost at best—to attract musical talent that could otherwise be based in New York or Los Angeles. Valera’s connection to Seattle was formed when a local group of Northwest musicians, which includes Seattle-based pianist Ann Reynolds, began traveling to Cuba to study Son with La Familia Valera Miranda. The only non-musician making these visits to the island was Wallingford resident Naomi Bierman, a veterinarian by trade.

“I was living in Cuba with my family and Naomi was a regular visitor to my hometown. We used to see each other in my venues, but just from far away. One day she came into my home. We started to talk because she was leading a group from Seattle that were recently in Santiago de Cuba, and she was like a tour guide or something,” recalls Valera.

Indeed, Bierman was along for the ride for other reasons besides Son music and dance. It didn’t take long for her and Valera to form a deep friendship based on trust.

“I would be the only person who went to Cuba, not for music or dance. But I’d be going, and then all the friends from here would pile on. They would all study with Kiki’s family. So, we were friends, but they were all studying with him,” says Bierman.

In a time when most Cubans were enduring a severe recession and living on $25 a month, Valera had earned decent money abroad playing music, receiving checks he could not cash in Cuba. He had stashed them under his mattress, amounting to tens of thousands of dollars. Valera solicited Bierman’s assistance: a helping hand that would require a high degree of trust between friends only recently acquainted.

“The royalty checks were from reputable sources, like Lloyds of London. But they were old, and hadn’t been cashed. The only scary part was they needed a hard copy of the check. So I did have to fax them the hard copies. If they were lost, that would have been it, but there was this karma thing,” she recalls.

That sense of trust, and the relationship that ensued would lead to their marriage and Valera’s arrival in Seattle. It has become a place to focus on his art, to deepen his journey into its traditional roots, while following the natural life currents of musical evolution.

Valera’s eagerness to learn about music outside of Cuba is quite a story in itself. At a time when American popular music was forbidden from Cuban airwaves, Valera endeavored to access broadcasts out of Jamaica on hand made radio sets he cobbled together out of random parts such as old television tubes. The location of Santiago de Cuba, his hometown, enabled access to these transmissions. He then became exposed to jazz, and the voices of artists such as Chick Corea, Wes Montgomery, and Pat Metheny became part of his personal musical narrative.

“I was intrigued,” he remembers. “The way they play, the way they improvise. I was curious, I had to learn. I had to understand what they were doing, because it was beautiful, like worship or something. And we started to listen. Figures like Chick Corea were my first experiences with that kind of music.”

Valera’s soloing on cuatro is ardently attached to Son tradition. His personal, identifiable striations within the form embolden a centuries old heritage, while daringly expressing his lifelong artistic curiosities. His innovative approach to Son is much like a jazz artist playing free, yet still referencing the blues and swinging hard. The innovation is within the form, not through disassembling and recreating it.

“I was born in Cuba and in Cuba you breathe Son. That is something that is in my DNA. I cannot play Son music, trying to, or pretending that I’m playing jazz. The roots are in me in a way where I don’t have to think. It comes out naturally. This is my mind, my intuition. I try to keep the balance in between those worlds, the roots of a song and the richness of the jazz world,” he says.

The complete tapestry of Valera’s life in music is ever present on Vivencias en Clave Cubana, a project completed with lifelong friend, vocalist/composer Coco Freeman. The two met at age eleven through music, and again in adulthood in Havana. This collaboration began long distance, eventually resulting in two studio sessions in Seattle.

Unlike many recordings of Son music one might chance upon that are virtually repertory performances of traditional tunes, this album features all originals by Freeman and Valera. Traditional in form and elegantly performed, the album, released on the Seattle-based Origin label, has the means to introduce Valera’s riveting style to a broad based international audience.

Valera celebrates his new album with a performance at the Royal Room, on December 13. He also performs regularly around town with Tumbao, and Mambo Cadillac.